//Words: 0

//Links: 0

//Words: 0

//Links: 0

It’s June 2020, in the middle of a global pandemic, massive protests against racial injustice are taking place around the world, carried out by the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. A revolution, the motives of which had built up for decades, was triggered by the police murder of George Floyd and started a new wave of protests with the appeal for legislative reforms against police brutality. In addition to verbal pleas, the demonstrations also engaged with the physical symbols of oppression. A chain of monument removals started, one of which was the destruction of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, England (fig.1). Some argued against the toppling with the position that monuments are artefacts with historical and cultural value. In response to the events, art historian Arnold Bartetzky writes, “Liberal societies should be able to endure that not everything that is in public spaces corresponds to our current world view. That is exactly what distinguishes us from dictatorships and autocratic regimes”1. But that doesn’t apply to Colton’s statue. The monument was put up in 1895, long after Colston’s death, thus it has nothing much to do with his life in the 17th century2. It was a historical ‘artefact’ that forces a specific interpretation of how the past should be perceived in the present. Monuments (from the Latin monere - to remind) are meant to withstand time and create open spaces to engage the viewers forcing them into creating associations3, by commemorating or even glorifying historical events and figures. This preservation of memory is a necessary practice in the formation of national identity. And in the case of Colston’s monument, the historical figure is mythologized to the extent of rewriting history, in order to sustain the idea of white supremacy in society. These intentions start to clash when the supposedly glorified figures have engaged in actions that were immoral or violent. Hence, the act of commemoration of the past through solid structures is regarded more critically by taking into consideration the truth and to what extent they (mis)represent history and our current values. In that sense, the engagement with the physical environment during the BLM protests rallies was an act that solidified their statement of breaking with the cycle of subjugation.

Having these events linger in my mind for almost two years, I started recognising links to my personal background. Born and raised in Bulgaria, a post-socialist country, after the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1989, I grew up around buildings and monuments that were reminders of a past ideology. It was a system that modelled society into controlled masses who trusted and served the state unquestionably, something that doesn’t apply to the current state of democracy. Some of the symbols of communism were demolished by the state, others were abandoned, slowly crumbling and losing their initial functions. But they still haunt people. Even people like me, who have never lived in the socialist era feel its presence through its residue. Public opinions about whether Soviet architecture should be demolished or preserved have been polarised4, tearing the image of these structures between a nostalgic memory and a horrid urban scrap. In my opinion, Soviet buildings, similar to the statue of Edward Colson, are solid structures linked, in one way or another, to the practice of gaining power through oppression. At first glance, these examples seem quite different. Colonial monuments exploit the past to sustain a certain ideology for present and future generations. On the other hand, Soviet culture halls, for example, are not intended as a commemoration of the past. They were rather borrowing ideas from the future. And within the Soviet context, they acted as a celebration of the present, bringing society together and further inspiring trust in the state. Both Soviet and colonial structures have been treated more like conceptual art pieces with a certain approach towards society. In our contemporary environment, Soviet buildings become either a direct portal to a past infiltrated with manipulation and oppression, or lose their intended role in modelling society, since the state is no more relying on populism.

In the meantime, the generation born after ’89 (including myself) dominates the art and pop culture scene– a field established through capitalist ideologies but situated in a hybrid urban environment of modern architecture and ruins of Socialism. An example of this mixed cityscape came from a recent trip to Moldova. My first impression of Chișinău formed at my arrival in a luxurious airport (fig.2). Once I left it however and headed towards the city, I was welcomed by the City Gates (fig.3), a complex of Soviet housing buildings, making the impression of gates that welcome the city’s guests. This fusion between the two realities reflected onto the presence of obsolete architecture is what I want to explore through this essay. I’m curious about the reappearance of the soviet building in modern (capitalised) pop culture in the form of aesthetics, a tendency that strips architecture off from its symbolism. How does the function of a building change through an ideological switch and through the prism of a generation that has never encountered the socialist regime? And is repurposing an art form, regardless of its initial concept, appropriating the historical and cultural relevance attached to it?

To fully understand the role of Soviet buildings (primarily in the period of late ‘60s to ‘80s), one should first look into the semiotics of architecture. Architecture constructs people's urban environment by creating or enclosing physical spaces, through which it establishes guidelines for movement and inhabitation. The topic of a building as a carrier of meaning is unfolded in Function and Sign: The Semiotics of Architecture where Italian historian and cultural critic Umberto Eco writes about architecture as a language for communicating ideas. Similarly to any object of use, a building is designed with a clear intention. It promotes a certain function5, which Eco defines as the denotation of the building or the “form of inhabitation”. Monuments in that case are intended as a commemoration of the past. The denotation of Soviet culture halls however is not initially commemorative, they are built to host cultural events, but similar to monuments, create space to engage the public. Apart from the denotation, Eco introduces the reader to connotative meaning, which signifies the ideology of the function6. A monument is not only meant to remind of the past. It also connotes power, pride and intent into the formation of national identity, something that also applies to the Soviet culture halls. On the surface, they require different means of use from the public, but they are both built with the intention to unite society around a certain paradigm.

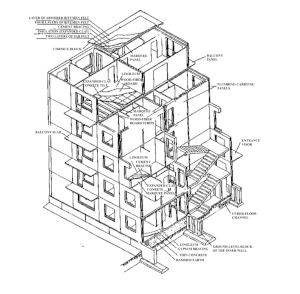

This encryption of meaning is achieved through codes, new unaccustomed elements that imply motives of meaning, even when the object is not in use. “One is not obliged to characterise a sign on the basis of either behaviour that it stimulates or actual objects that would verify its meaning: it is characterised only on the basis of codified meaning that in a given cultural context is attributed to the sign vehicle.” writes Eco7. Therefore if a building’s meaning is codified in the structure, thus solidified in the entirety of the building, the ideology becomes encapsulated, able to withstand time, unattached from the inhabitation. An example of this ideological implementation is the 1960s Khrushchyovka (fig.4). Named after the Soviet leader at that time, Nikita Khrushchev, the type of building came to dominate housing planning all over the USSR and the countries from the Soviet bloc. These concrete-panel buildings were cheap and easy to build. The fact that they provided equal (and relatively small) living space to the working class was the reason why they became the ideal embodiment of the Communist ideology. Even today, the small cells still remind and represent the Socialist ideals– equality, community and sustained life standard by the state. What has changed is the comprehension of these ideas by the younger generation. What I would argue for is that a building’s connotation hasn’t diminished over time, but that it has acquired new meanings. Instead of a symbol for equality and community, now the Khrushchyovka appears in music videos of artists like the Belarusian band Molchat Doma (fig.5) who use it to visualise topics around political stagnation and social crisis in Eastern European countries.

In Architecture and Utopia: The Semiotics of Architecture Manfredo Tafuri suggests that “architecture, at least traditionally conceived, is a stable structure, which gives form to permanent values and consolidates urban morphology.”8 For that matter, it is the perfect tool for the visual manifestation of political, religious, or cultural dogmas. And indeed it was one of the tools used for political propaganda of the Socialist State. Here it is helpful to define the differences between ideology and political reality in the Soviet bloc. Communism is a theory of systems for social organisation, based on the Marxist ideas for complete disregard of social classes and collective over private ownership. The doctrine describes different stages of the system, with Communism at its highest level, where the worker is fully devoted to the state with disregard to any personal material needs. However, for such a socio-economical system to be executed, it would require strong faith in the ideology and determination to the state. Else, it is considered to be purely utopian.

Utopia, from Greek ou-topos (οὐ τόπος), refers to ‘no place’ or ‘nowhere’, similar to Greek eu-topos (εὖ τόπος) meaning ‘good place’.9

Utopia describes an imaginary society that possesses highly desirable qualities.10 To reach that desirable place, Soviet society had to endure Socialism first. But since in reality the socialist era didn’t achieve complete Communism, it came to be perceived as a period of nothingness, a void filled with ideology and promises, implied through utopia.11 As the only drive for the political model becomes a sole intellectual construct, that construct has to be massively manifested to sustain society’s interest. That’s where architecture accepts the task of politicising its own handiwork. How George Jepson puts it in the essay “Recourse to Utopia: Architecture and the Production of Sense without Meaning”: “As agents of politics, architects had to take up the challenge of continuously inventing advanced solutions at the most generally applicable levels. Toward this end, ideology played a determinant part.”12 This type of architectural propaganda became very prominent during the Stalinist era.13 Architects like Boris Iofan, El Lissitzky and Ivan Leonidov were creating designs with the intentions of sustaining the state’s ideology (fig.6). A well-known architectural piece was Iofan’s Palace of the Soviets, which was an ultimate symbol of dominance during the Stalinist era. The absurdity with this construction is the intended size and elevation, positioning the state as rather ruling from above than constituted from below. Through these imagined structures, the imperialist nature of the system is already noticeable, which contradicts the constituted Marxist ideas. However these visual masterpieces were never built, only labelled “paper architecture”.

Realised Soviet architecture naturally included grandiose monuments of Vladimir Lenin or Joseph Stalin, as a celebration of the Communist leaders, as well as of the working class, like the Worker and Kolkhoz Woman (fig.7). However, most of the ideological dogmas were implemented in the communal accommodations, facilities and even bus stops. There was an emphasis on facilities for leisurе (fig.8), where the workers could rest and return recharged and more productive.14 The social model was deeply embedded into the daily routines of the citizen, as Boris Groys puts it, “the historical accomplishment of communism lies precisely in how it transformed actual society into a political model.”15

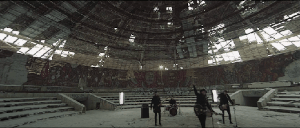

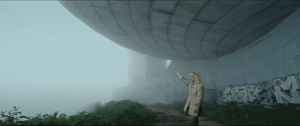

One particular example I relate to on a personal level is the Buzludzha monument, the House of the Bulgarian Communist Party (fig.9). This concrete and steel masterpiece, resembling a flying saucer followed the ’60s Soviet achievements in outer space. The structure was one of many that expanded visually on the dreams and promises for a utopian future. The opening of the monument in 1981 was a euphoric moment for the general public. The event was also an opportunity for the state to strengthen society’s beliefs in the communist party and its ability to turn futuristic promises into reality. This trustful image of the party was commonly sustained through the grandiose architectural achievement of the time. The Buzludzha monument took eight years to build. It also remained for eight years, until 1989, when the Soviet Union collapsed and so did the ideology manifested through the concrete architecture.

30 years after these events, remnants of Soviet architecture are still part of the urban environment, haunting the present with memories from a bittersweet past. In The Post-Communist Condition Groys writes: “The place of the communist Utopia once lay solely in the future; today the place of communism lies in the past.”16 And so are the monuments that were once a glimpse into the future. Now they are only a ruin, turning the utopian dreams encapsulated in them into an unfulfilled promise from a past era. These structures still carry encoded symbols of the communist ideology. This makes them alien to their current surroundings: a world built around a completely different paradigm. They were physically and ideologically abandoned, yet didn’t undergo full demolition. Their leftovers now also belong to the generation born after ’89, a generation, which never endured any of the indoctrination around architectural symbols. This switch in the political environment together with a generational shift causes a change in the public perception as well as the role of the buildings.

This reshaped meaning of Soviet architecture is apparent in the film When the Earth Seems to Be Light (2015). Situated in post-soviet Georgia, the film is a collection of impressions by a group of skateboarders on the current political climate and the environment they’re stuck in. Besides the stories they share, the characters are on a constant search for grey areas to create their own spaces of existence, inhabiting abandoned spaces and using the concrete structures for skateboarding (fig.10). The visuals of ruins strengthen the stories of the corrupt political environment, stemming from the socialist era. Current political notions however are no longer masked under symbols of utopia and dreamy prospects for the future. Now as Soviet ideology has left politics, the destruction of utopian symbols only signalises the loss of future in the country. Ruins become a shelter to people, searching for an escape from reality in forgotten buildings that were once envisioning unimagined realities. In that sense Soviet architecture already gains new connotations, becoming a backdrop to younger generations’ dreams for better (newly utopian) realities and their “romantic notions of free existence”17. It almost acquires a binary meaning: a dystopian space depicting the ongoing socio-political transition and traces from a flawed socialist system, as well as a romanticised space for escapism.

As part of the post-Communist generation, I have also encountered the shift in the meaning of Soviet buildings as well as the generational gap in perception of their role in our modern society. The Khrushchyovka style buildings were a consistent part of my childhood environment, as well as the stories of my family about the sublimity of the Soviet era, an idyllic picture of safety and exciting experiences. But to speak of safety is an exclusive privilege of the party members, and to believe in the indulgence of possibilities is an illusion created by censorship. The stories would be told with exhilaration, praising Socialist architecture as if society’s perception of reality was impaired by decades of propaganda and manipulation. The discussions would circle around the variety and comfort of summer resort accommodations, but there was also a place for admiration for the monumental buildings and pavilions that the Soviets designed and built, like the marvellous space saucer of Buzludzha.

30 years after the fall of Communism, the Buzludzha monument is still standing tall on the mountain hill where it was once abandoned. The building was looted and partly destroyed in the ‘90s, but mostly it has suffered a slow decay over the years. Like my family, many Bulgarians to this day glorify the monument and its past, others consider it a useless ruin, a leftover of an oppressive era. While heated discussions over the worth of the building continue, a foundation for preservation initiated the Buzludzha project– a program aiming to halt the destruction of the interior mosaic artworks and restore the monument. Yet even their motives supporting the initiative are not convincing enough. It creates a paradox for the monument’s role as a communist symbol and one of transition to democracy, as a symbol of creating conflicts, yet unifying people.18 In regards to the project, what I argue against is not the historic, architectural and cultural significance of the building, but rather the ignorance towards the monument’s past.

This lack of acknowledgement occurs in both former Communist and post-Communist generational perspectives. While the majority of people, who endured Socialism, long for the past, their nostalgia affects their sensible perception. They see these Soviet buildings through a selective memory, as what they used to be– astonishing pieces of architecture made possible by the Soviet state. But this only creates dissociation with the present and the realistic position of the buildings in modern urbanism and society. On the other hand, the post-communist generation overlooks the encrypted symbolism in the architecture and instead builds its own romanticised and aestheticised world around it.

The reason for this detachment of Soviet remnants from the ‘problematic and controversial’ label is the distant involvement in the act of subjugation. Back to the comparison with the Edward Colston monument, the implied and perceived symbolism of Soviet architecture differs from colonialist statues. The latter were ones of historical figures that engaged directly in immoral practices, similar to the Lenin and Stalin monuments which were demolished with the fall of Communism. Utopian architecture however doesn’t hold on to the same negative connotations, it was built to accommodate the worker in their daily life. But through its design, it came to be a carrier of utopian ideologies, which acted as a supporting system for society’s trust in Socialism. Ideally, architecture was a proxy of the doctrine, doubling as a distraction to the oppressive and corrupt reality of the political regime. This characteristic sets it apart from other problematic monuments by forming a grey area for its present existence.

In contrast to the former communist generation, the post-communist one isn’t influenced by the ideology and propaganda engraved in these obsolete structures. The shift in perception had also something to do with the shift in the political system and the beginning of the so-called ‘transition’. The Post-communist age was defined by loss of identity. Until that point identity was shaped by the socialist coercion, but after ’89 became a subject to neoliberal capitalism.19 While the subjects of post-communism struggled towards finding a sense of self, outside of the community and the state, they were pushed into re-creating themselves in an environment that was still dominated by communist dogmas. This was only a catalyst to capitalising leftovers from an ideology.

The topic of capitalism’s role in eradicating the historical and cultural value of architecture is unfolded in the short film Exile Exotic (2015) by Sasha Litvintseva. The film narrates the story of Moscow’s Kremlin and its sized down replica, which exists as a holiday resort in Antalya, Turkey (fig.11). It is a reflection on the uncanny fusion of a monument’s symbolism and hotel aesthetics. The original architectural piece is not considered Soviet architecture. However, its history is entangled in conflicts of politics, ideology and religion creating an indirect correlation with Soviet monuments’ symbolism and their metamorphosis in a capitalist age. Both have lost their identity hence their initial codified meaning, becoming an empty body controlled by the market and the consumer’s desires. While the Kremlin underwent self re-creation into an object fitting the capitalist model, most Soviet buildings were left into decay, which turned them into an aestheticised piece to younger generations.

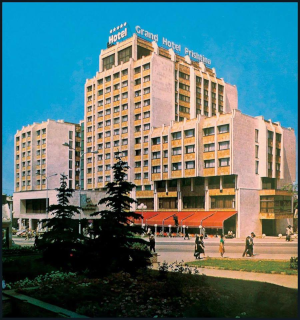

An example of the capitalisation of Soviet remnants is the Grand Hotel Pristina in Kosovo (fig.12). It was considered one of the most esteemed architectural projects in former Yugoslavia, projecting power and progress through its appearance.20 The Grand Hotel was turned into the “city’s societal hotspot” in the 80s by ideally fusing politics with social aims.21 After the end of Communism and the split of Yugoslavia, the building was privatised and lost its past identity. The hotel still exists to this day, surfacing on the internet with disappointing online reviews. Part of the building however has been kept alive through the emergence of 13 Rooftop– a nightclub situated on the top floor of the hotel (fig.13). This fusion of modern-day party culture with the gruesome concrete structures of a dilapidating Soviet building seems very unsettling at first, yet has become the reality for the post-communist generation.

This phenomenon is manifested through the term ruin porn– a concept that Exile Exotic glimpses at. What ruin porn conveys is the visual appeal of abandoned buildings and structures that had a future in the past but now only exist as lost ambition. Similar to what socialist utopia is. The concept is not as commonly observed in the physical inhabitation of Soviet remains but rather in how they are perceived and communicated. Architecture is being capitalised by the fastest growing market among young people– internet pop culture. Social media platforms become home to abandoned structures (fig.14). There they can be encapsulated with new meanings, formed by the same environment and the consumers entering it.

The inevitable act of re-identification through commodification descends even more when the ‘West’ takes over. Architectural pieces like the Buzludzha monument become capitalised by the western music and film industry. Hence their historical and cultural significance is not only neglected but twisted into a new disconnected narrative. In some cases, they are played as a proxy for the ‘Soviet’ or ‘Russian’ identity. In others they are completely stripped of their symbolism and downplayed as a pure form of aesthetic, being further romanticised or even poeticised (fig.15). In the effort for re-establishment of Soviet architecture, pop culture turns into a faux lifebelt helping it resurface. Instead of re-introducing it realistically, it reshapes it to fit the modern capitalist environment. Through this act, the codified ideology is rather buried and forgotten than acknowledged and taken into account. This only proves that capitalisation of Soviet remnants is an appropriation of their cultural and historical value. Furthermore, it forges a false representation of an architectural piece, which deludes society into how to perceive and exploit it.

Architecture, similar to any existing object or piece of art, is built with a certain intention, either purely functional, infused with ideology, or in the case of Soviet architecture– both. While art can certainly be viewed through the lens of personal interpretation, the political and cultural environment it has evolved in, establishes its larger meaning. It is the codified meaning that surpasses time and change through the body it is encapsulated in. With that being said, Soviet architecture was created as a physical extension of the communist ideology that reaches out and occupies the social realm. It becomes a direct link to the proclaimed dogmas of the Soviet state, which surge into the prospects for a utopian future. This viewpoint disproves the possible link to the acts of oppression, manipulation and injustice exercised by the state. This explains why they haven’t been destroyed but left into decay.

In the current day and age, these Soviet structures still represent the same utopian dreams and prospects but are rather seen as unrealised ambitions of the past communist state. In reality, this symbolism has been stripped away, remodelled or morphed to fit capitalist desires. Soviet architecture is forced into a new meaning. For the Post-Soviet generation, the structures become a symbol of the contemporary socio-political reality of corruption and stagnation. But with the development of pop culture and through western influence, it becomes exploited only for its appearance. This capitalisation of symbols, regardless of their ideology, is comparable to cultural and historical appropriation. It introduces a false representation of architecture with a socio-political value and creates a cycle of ignorance.

It is natural that the identity of a structure would fade away over time, especially when the purpose it was meant to serve is no longer viable in a new political environment. However, from my standpoint as a graphic designer, I approach any symbol, whether art or architecture, as a carrier of ideas through time. Even if a building loses relevance or specific, intended meaning, the job of a designer is to repurpose it in a form that justifies its historical significance in our present. I would argue for a multi-generational perspective on the meaning of obsolete structures in order to bridge the gap between differing experiences and points of view. Rather than using structures mindlessly as a backdrop, it could become the main character, telling а story of the social metamorphosis, from members of a united nation to ego-driven individualists. I started this research fascinated by the complexity of Soviet architecture. But it remains a challenge to imagine how I could preserve and repurpose these remnants as a graphic designer, without causing any further damage.

© Studio Polina Slavova 2025